Correia da Serra’s association with European scholarly circles does not seem to have helped him much in dealing with political pressure, as he had to flee from Portugal a second time in 1811. On this occasion, he chose the United States of America, no doubt because he was an admirer of the liberal ideas associated with the founding of the American republic.

Carrying with him letters of introduction from well-known European and American intellectuals, some of whom he had met during his Parisian exile, such as Joel Barlow, David Warden, Alexander von Humboldt and the Marquis of Lafayette, he arrived in Norfolk, Virginia, on February 21, 1812. From there he went on to Washington, where, using Barlow’s letter of introduction, he met President James Madison, as well as Albert Gallatin, his Secretary of the Treasury. With the help of Gallatin he wrote a letter introducing himself to former President Thomas Jefferson, with whom he was to develop a close relationship.

Correia da Serra’s first visit to Monticello took place in the summer of 1813, and he immediately caused a strong impression on the former American President. In a letter written to Caspar Wistar, physician and anatomist, as well as professor at the University of Pennsylvania, dated August 17, 1813, Jefferson had this to say about Correia da Serra: “I found him what you had described in every respect; certainly the greatest collection, and best digest of science in books, men, and things that I have ever met with; and with these the most amiable and engaging character”.

During his American sojourn, Correia da Serra was a frequent visitor to Monticello as he clearly shared with Jefferson political and scientific interests. They are credited, for instance, with having sketched out a plan whereby the United States and Portugal would divide the New World into two areas of influence, one under the control of the U.S. and the other of Portugal, a reborn nation, now with its capital in Rio de Janeiro.

Jefferson’s “American System”, as the project was called, involved the separation of the Americas from European influence. In a letter sent to President Madison, dated 10 July 1816, for instance, the Abbé described the plan in these terms: “Our nations are now in fact both American powers, and will always be the two paramount ones, each in his part of the new continent” (Serra apud Davis 202). But John Quincy Adams, who headed the State Department in the administration of Monroe at the time, was not convinced, as this would certainly weaken America’s ambitions in the New World. It is rather doubtful (and unrealistic) to think that this grand idea of an American System to be established between Portugal and the United States, with its centers of power in Rio and Washington, respectively, could ever be implemented, as it did not reflect the geopolitical realities of the time. In scope, this plan would have almost amounted to a new Tordesilhas Treaty.

in The Powerless Diplomacy of the Abbé Correia da Serra, Edgardo Medeiros Silva. ULICES - University of Lisbon Centre for English Studies Technical University of Lisbon

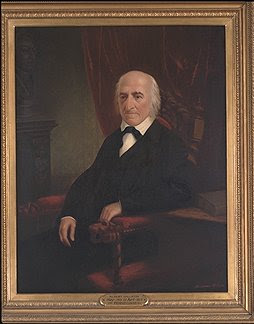

Albert Gallatin

GALLATIN, Albert, a Representative and Senator-elect from

Pennsylvania; born in Geneva, Switzerland, January 29, 1761; was graduated from

the University of Geneva in 1779; immigrated to the United States and settled

in Boston, Mass., in 1780; served in the Revolutionary Army; instructor of

French in Harvard University in 1782; moved to Virginia in 1785 and settled in

Fayette County (now in Pennsylvania); his estate becoming a portion of

Pennsylvania, he was made a member of the Pennsylvania constitutional

convention in 1789; member, State house of representatives 1790-1792; elected

to the United States Senate and took the oath of office on December 2, 1793,

but a petition filed with the Senate on the same date alleged that Gallatin

failed to satisfy the Constitutional citizenship requirement; on February 28,

1794, the Senate determined that Gallatin did not meet the citizenship requirement,

and declared his election void; elected as a Republican to the Fourth, Fifth,

and Sixth Congresses (March 4, 1795-March 3, 1801); was not a candidate for

renomination in 1800; appointed Secretary of the Treasury by President Thomas

Jefferson in 1801; reappointed by President James Madison, and served from 1801

to 1814; appointed one of the commissioners to negotiate the Treaty of Ghent in

1814; one of the commissioners who negotiated a commercial convention with

Great Britain in 1816; appointed United States Envoy Extraordinary and Minister

Plenipotentiary to France by President Madison 1815-1823; Minister

Plenipotentiary to Great Britain 1826-1827; returned to New York City and

became president of the National Bank of New York; died in Astoria, N.Y.,

August 12, 1849; interment in Nicholson Vault, Trinity Churchyard, New York

City.

Albert Gallatin, best known as President Thomas Jefferson’s secretary of the Treasury, opposed the U.S. Constitution because he feared the loss of individual freedoms under it. He remained concerned about civil liberties, including those in the First Amendment, once the Constitution was adopted.

Born into a prominent family in Geneva, Switzerland, Gallatin lost his parents and his only sibling during childhood. He graduated from Geneva Academy in 1779 and emigrated to the United States in 1780, partly because he liked the new nation’s liberal political values.

Gallatin thought new Constitution did not adequately protect individual liberties

Gallatin first became active in U.S. politics in August

1788, when Pennsylvanians opposed to the proposed federal constitution met to

argue against ratification. Conceding the need of a central government for

protection from without and from within, Gallatin criticized the elements of

the proposed document because he thought that it did not sufficiently protect

individual liberty from concentrated power

He specifically wanted to limit the authority of the executive and judicial branches because they would be further from the people and, therefore, more susceptible to corruption and abuses. He wanted the House of Representatives to be large enough to repel special interests and to protect itself against the Senate.

Gallatin served in the Pennsylvania state legislature from

1790 to 1792. He advocated a system of public education, but also displayed his

lifelong interest in financial matters, supporting bills to abolish paper money,

pay the public debt in specie, and establish a bank of Pennsylvania to help

support business endeavors.

Pennsylvanians elected him to the U.S. Senate in 1793, but Gallatin was denied his seat, ostensibly because he had not been a U.S. citizen for nine years. Evidence suggests that his anti-Federalist activities were also to blame.

In 1794 the Whiskey Rebellion began in western Pennsylvania, and President George Washington moved quickly to put it down. Gallatin feared that the combination of a uniformed governmental presence along with the repression of public opinion could lead to dissolution of the Union. He also expressed concern that a vengeful military could turn on the citizenry. He argued that a free government should have authority that rests upon the consent of the people rather than force and oppression. Nevertheless, Gallatin urged the rebellious farmers to submit to government taxation.

Gallatin continued his political career by serving in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1795 to 1801.

In 1797 he became the leader of the Republican minority. He insisted that the Department of the Treasury be accountable to Congress and played an instrumental role in creating a standing committee on finance.

Gallatin was among the Republicans who opposed the adoption

of the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798, the latter of which abridged freedom of

speech and press. His skill at party organization helped Jefferson win the presidency,

and in 1801 Jefferson appointed Gallatin to head the Treasury.

Gallatin supported westward expansion and, pacific by nature, strongly encouraged the Louisiana Purchase as a means of avoiding war. He insisted that trial by jury, freedom of religion, and freedom of the press be established in the newly acquired territory.

Gallatin spent 12 years as Secretary of the Treasury, a record that has yet to be surpassed. He concerned himself chiefly with balancing the budget and reducing the national debt.

After Gallatin left the cabinet, President James Madison sent him to Russia, in 1813, to discuss the czar’s offer to mediate a settlement of the War of 1812. In 1814 he helped draft a peace treaty as a member of the U.S. Peace Commission at Ghent. Gallatin then served as U.S. envoy to France from 1816 to 1823 and to Great Britain from 1826 to 1827. He concluded his public service as president of the New York branch of the second Bank of the United States from 1831 to 1839.

In retirement, Gallatin continued to show his concern for

individual liberties. He opposed the U.S. takeover of Oregon and American

involvement in Mexico in the 1840s as acts of aggression that threatened

freedom. By the time of his death, Gallatin’s contemporaries ranked him only

slightly below Washington, Jefferson, and Madison in service to his country.

This article was originally published in 2009. Caryn E. Neumann is an Associate Teaching Professor at Miami University of Ohio Regionals. She earned a Ph.D. from The Ohio State University. Neumann is a former editor of the Federal History Journal and has published on Black and women's history.

in https://www.mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/1161/albert-gallatin

Albert Gallatin was born on January 29, 1761, into a wealthy family in Geneva, Switzerland. His parents both died before he was ten and he was raised by a cousin. Graduating from the University of Geneva, Gallatin emigrated to the United States in 1780, becoming a U.S. citizen in 1785. In his first decade in America, he taught French at Harvard, worked as a land speculator throughout the mid-Atlantic, developed a life-long fascination with Native American culture, sought the abolition of slavery, and was widowed after only five months of marriage.[2]

In the 1790s, Gallatin settled in Philadelphia and immersed himself in politics. It is likely that Jefferson first met Gallatin at the American Philosophical Society where they were both members.[3] Gallatin's 1793 marriage to Hannah Nicholson (daughter of retired Navy Commodore James Nicholson, a key figure in the Democratic-Republican movement) elevated his social and political standing. Aligning himself with Jefferson's emerging Democratic-Republican party, Gallatin was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1794 and developed a reputation for mastery of public finance and opposition to Alexander Hamilton's policies. In his three terms in office, he helped establish the House Ways and Means Committee and rose to become the Democratic-Republican leader.[4]

In the 1800 presidential election, the Democratic-Republican party won a clear victory over the Federalist party. The Federalists devised a plan to deny Jefferson the presidency in favor of Aaron Burr, the Vice-Presidential candidate, creating a Constitutional crisis that forced the decision into the House of Representatives. Working behind the scenes for Jefferson, Gallatin wrote his wife, "We have this day, after 36 ballots, chosen Mr. Jefferson President. Thus has ended the most wicked and absurd attempt ever tried by the Federalists."[5] As President, Jefferson chose James Madison as Secretary of State and Albert Gallatin as Secretary of the Treasury. They would become his key advisors in the "Revolution of 1800."[6] Among Gallatin's accomplishments as Treasury Secretary, he eliminated Federalist taxes, reduced the national debt, commenced programs for internal improvements, secured financing for the Louisiana Purchase, and made an enduring contribution to the separation of powers within the U.S. government by requiring specific appropriations of funds by Congress to implement government policy.[7]

In Jefferson's two terms as President, Gallatin emerged as the most influential member of his cabinet. The harmony that they developed, in order to achieve the administration's goals, is reflected in Gallatin's remark to Jefferson:

Of your candour and indulgence I have experienced repeated proofs: the freedom, with which my opinions have been delivered, has always been acceptable and approved, even when they may have happened not precisely to coincide with your own view of the subject, and you have thought them erroneous.[8]

Jefferson rarely held full cabinet meetings, preferring to meet cabinet officers in private during the workday. In Gallatin's case, Jefferson wrote, "perhaps you could find it more convenient sometimes to make your call at the hour of dinner … you will always find a plate & a sincere welcome."[9] Their professional relationship evolved toward a deep friendship.

In his second term as President, amidst deteriorating relations with Great Britain, growing out of the Napoleonic wars and British impressment of American seamen, Jefferson believed economic sanctions would avoid war and bring Britain to the bargaining table. Gallatin opposed these measures, cautioning Jefferson, "Governmental prohibitions do always more mischief than had been calculated; and it is not without much hesitation that a statesman should hazard to regulate the concerns of individuals as if he could do it better than themselves."[10] Jefferson, however, overruled Gallatin, who then faithfully enforced embargos on American-British trade. These sanctions failed to achieve their purpose, sowed discontent with the American public, disrupted the American economy, reduced government revenue, and damaged both Jefferson's and Gallatin's reputations.[11]

Succeeding Jefferson as President, James Madison was unable to gain support for Gallatin to be Secretary of State and his cabinet did not enjoy the harmony of Jefferson's. Gallatin stayed on as Treasury Secretary, presiding over America's precarious finances under conditions that were made worse by Madison. The President refused to endorse Gallatin's demand that Congress renew the charter of the Bank of the United States and he failed to offer policy guidance to his cabinet to steer America away from war. Gallatin's relationship with Madison deteriorated as well and he tendered his resignation informing Madison, "Measures of vital importance have been and are defeated: every operation even of the most simple and ordinary nature is prevented or impeded: the embarrassments of Government, great as from foreign causes they already are, are unnecessarily encreased: public confidence in the public councils and in the executive is impaired; and every day seems to encrease every one of those evils."[12] On the brink of war, Madison retained Gallatin. During the War of 1812, Gallatin shored up the nation's finances at the cost of tripling the national debt which put an end to his financial reforms and plans for internal improvements. Stepping down as Treasury Secretary in 1813, Gallatin devoted himself to ending the War of 1812, culminating in the Treaty of Ghent in 1815. Gallatin's final service to the Madison administration was recovering America's financial standing by convincing Congress to charter the Second Bank of the United States.

In James Monroe's administration, Gallatin served as Minister to France from 1816 to 1823, where he aided in negotiating the Rush-Bagot Treaty and Treaty of 1818. Called out of retirement in Pennsylvania by President John Quincy Adams, Gallatin served as Minister to the United Kingdom in 1826-1827. Ending a political career of almost four decades, Gallatin moved to New York City where he served as president of the National Bank of New York from 1828-1839 and founded New York University in 1831. In 1842, Gallatin's life-long fascination with Native American culture led to his founding of the American Ethnological Society, setting the groundwork for the modern study of anthropology.

Gallatin died on August 12, 1849, having devoted his life in service to his adopted country, and fulfilling Jefferson's assessment of him when he wrote, "I believe mr Gallatin to be of as pure integrity, and as zealously devoted to the liberties and interests of our country as it's most affectionate native citizen."[13]

Albert Gallatin

Carta do Abade Correia da Serra a Thomas Jefferson, referindo Gallatin:

Washington city 6 March. 1812

Sir

When i Left Europe two months ago, several of your

correspondents and friends in that part of the world favoured me with Letters

of recommendation to you, knowing how ardently i wished the honour of your

acquaintance. Mr Thouin gave me also his Last publication on grafting, that i

might present to you on his part. Not having the advantage of finding you in

this place as i was Led to believe in Europe, and being obliged to go as soon

as possible to Philadelphia where i intend to reside, i send you Mr Thouin’s

book, that you may not be deprived of the pleasure of reading it, and keep the

Letters with me, which i shall have the honour of presenting to you in the

course of this summer when i intend to undertake the pilgrimage of Monticello.

The present Letter and Mr Thouin’s book i leave here at the care of Mr

Gallatin. I am most devoutedly

Sir Your most obedient he servt

Joseph Corrêa de Serra

in https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-04-02-0431

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário